Spanning across the borders of Andhra Pradesh, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Maharashtra, and Rajasthan, a territory traditionally called "Rewakantha" (a Gujarati term for the drainage of the Narmada River, also called Rewa), is the homeland of people collectively known as the Bhils. Belonging to the race of pre-Aryan civilization, Bhils, considered one of India's ancient tribes, reside in the forested lands of Vindhya and Satpura hills and in pockets of western Deccan regions, eastern Tripura, and the Tharparkar district of Sindh, Pakistan. Renowned for their distinctive art, particularly vibrant wall paintings and intricate tattoos, the Bhils' artistic expressions are deeply rooted in their cultural heritage and natural surroundings.

Origins

Bhil mythology traces their ancestry to Nishada, the son of the god Siva and his human lover who was exiled to the mountains after killing his father's bull, where the Bhils have resided ever since. However, many historians believe that the Bhils descend from the earliest settlers of northern India. Some scholars theorize their origins to the Harappan civilization that inhabited the Indus Valley from 3500 to 2500 BCE. During the second millennium BCE, the Indo-Aryan incursions forced the Bhils to the high grounds, which were easier to defend. The years of the invasions led to the assimilation of Indo-Aryan customs and practices in the Bhil culture.

In the medieval Indian subcontinent, Bhils became proficient in using bows and arrows, which helped them fight guerrilla wars against groups like Rajputs who invaded their lands. As a result, many scholars believe that the tribal name, 'Bhil', is derived from the Dravidian word for villu or billu, meaning bow. No wonder the tribe also traced their lineage to Eklavya, the skilled archer in Mahabharata. The Bhil archers of the Alirajpur district in Madhya Pradesh continue to use the no-thumb tradition while learning archery as a symbolic honour to Eklavya and protest against the injustices of Dronarcharya and Arjun.

Moreover, the Bhil communities hold significant mentions in ancient scriptures such as the epic of Ramayana. In this revered tale, the story of Shabri, a Bhil woman, unfolds as she offers jujube fruits (ber) to Lord Rama during his arduous journey through the dense jungles of Dhandaka in search of his beloved wife, Sita. Adding to that, Bhil mythology also believes that Valmiki, the author of Ramayana, was a Bhil himself. Even in Sanskrit literature, an intriguing account surfaces, describing a Bhil chief bravely mounting an elephant to oppose the advance of another king through the formidable Vindhya Mountains—a story immortalized in the Katha-Sarit-Sagar (600 A.D.).

Religious History

In each village, there is a local deity known as the Gramdev, and families have their own household deities like Jatidev, Kuldev, and Kuldevi, represented by symbolic stones. The Bhils also worship serpent-gods, Bhati dev and Bhilat dev, as well as Baba dev, their village god. They have specific gods for crops (Karkulia dev), pastoralism (Gopal dev), lions (Bag dev), and dogs (Bhairav dev). Other deities revered by the Bhils include Indel dev, Bada dev, Mahadevel, Tejaji, Lotha mai, Techma, Orka Chichma, and Kajal dev.

The Bhils hold strong superstitious beliefs and exhibit deep faith. While they primarily identify as Hindus, as mentioned in researcher Victoria R. Williams's volume Indigenous People: An Encyclopedia of Culture, History, and Threats to Survival, the Nirdhi Bhils of Maharashtra follow Islamic philosophies, and some members of the Tadivi Bhil subgroup also adhere to Islam. Additionally, some Bhils follow their own religion called Sonatan, which blends Hindu beliefs with animistic philosophies, as claimed by Williams.

History

During medieval India, the Bhils fought to maintain political power and preserve ancestral lands. After losing control, they retreated to jungles and hilly areas, establishing small states. However, ongoing wars with the Rajputs, Mughals, and Marathas resulted in the looting and annexation of their forested territories.

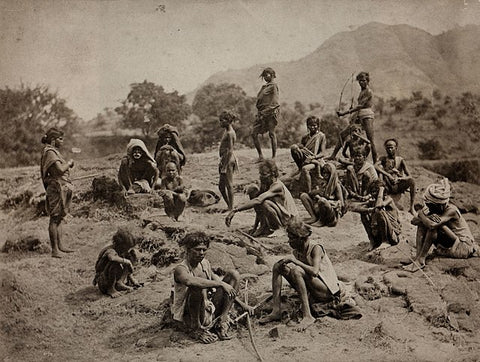

In the pre-Independence era, the Bhils faced exploitation and served as bonded laborers under colonial rule. The great famine of 1899-1900 exacerbated their plight, leading some Bhils to resort to banditry for survival. The British administration viewed the Bhils as wild and attempted to subdue them by aiding non-Adivasi elites, dividing and ruling through alliances with willing chieftains, and employing brutal reprisals against Bhil raids. This oppression caused more Bhil uprisings.

From the mid-19th century onwards, the colonial presence intensified in the region, with fiscal policies imposing taxes on Bhil cultivators and enclosures of forests. The Bhils were forced into settled agriculture, leading to debt and taxation issues. The Bhil warriors continued to resist the British, migrating to higher ground to evade taxes and conscription. Meanwhile, those who adhered to animist beliefs faced conversion attempts by Christian missionaries.

Under the Criminal Tribes Act of 1871, the Bhils, along with other social groups, were labeled as criminal tribes, subjecting them to arbitrary arrests, torture, and killings by colonial authorities. The Bhils protested against various injustices in 1881, such as census classification, alcohol prohibition, and the ban on witch killings. In 1883, Govind Guru, a social and political figure emerged as a leader for the first Bhil agitation called the Bhagat Movement. According to Indian historian Ram Pande, Govind Guru, through his long-term Brahminical Hinduism missionary work among the tribe, successfully halted their consumption of meat and alcohol. The heart of this protest unfolded in Dungarpur and Banswara, where the Bhil community resided in significant numbers. Their primary grievance was directed toward the bonded labor system enforced by the princely states under the British Raj. One significant event was the Mangarh massacre on November 17, 1913. British and Indian troops attacked the stronghold of Govind Guru, situated on a hillock in the Mangarh Hills of Rajasthan. The exact number of Bhil casualties remains uncertain, with estimates ranging from "several Bhils" to an oral tradition claiming 1,500 tribals were killed.

Even after the Bhagat movement, oppressive policies against the Bhils persisted. In 1917, Bhils and Garsiyas wrote a letter expressing their frustration to the Maharana of Mewar, citing exploitative policies, particularly the forced labor system. In 1920, the Eki Andolan was initiated at a place called Matrkundia, led by a Gandhian disciple Motilal Tejawat. The Bhil community presented twenty-one demands to the Maharana of Mewar, who accepted eighteen of them but rejected three major demands related to wood collection, grass collection, and hunting swine. Mahatma Gandhi, however, distanced himself from Tejawat's beliefs, as expressed in an article in Young India.

On March 7, 1922, thousands of protesters gathered in Palchitaria village in Idar State to rally against bonded labor. Major H.G. Sutan, commanding the Mewa Bhil Corps, ordered firing, resulting in a massacre where 1,200 people were shot dead, and two wells were filled with the martyred tribals. Known as the Palchitaria massacre, it occurred three years after the Jallianwala Bagh incident. Although the Maharana of Mewar eventually accepted the Bhils' demand to regulate bonded labor due to this incident, it never received due recognition in history. Balwant Singh Mehta, a freedom fighter and Tejawat's colleague, attributed this lack of acknowledgment to the victims being poor and illiterate tribals, as well as the British government's efforts to suppress the incident due to the flack they received during the Jallianwala Bagh tragedy. It is presently referred to as the Adivasi Jallianwala.

In the latter half of the 20th century, some Bhils who had migrated to upland areas moved back to lowland regions and took up agriculture and animal husbandry. Others remained scattered across upland areas. Bhil warriors were integrated into the Bhil Corp of the British military, allowing the British to keep a close watch on Bhil activities while permitting the Bhil to have their semi-autonomous state. This arrangement was negotiated between the British and a Bhil chief named Kumar Vasava of Sagbara. Initially, the Bhils practiced slash-and-burn (jhum) farming, but the Government of India post independence in the 20th century banned this method to prevent deforestation. As a result, the Bhils adopted settled agriculture. However, their land is often water scarce, leading to occasional conflicts with neighboring communities and the tribe. This also led to rising support for the demand of Bhil Pradesh.

The Demand for Bhil Pradesh

Image Credits: Caravan Magazine

The first call for a separate Bhil Pradesh gained momentum following the Mangarh massacre, led by Govid Guru. The Bharatiya Tribal Party (BTP) was established in 2017 in Gujarat by Chhotubhai Vasava and advocated for the creation of Bhil Pradesh—a separate state comprising 39 districts across Gujarat, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra. Chhotubhai Vasava, along with a delegation, even presented a memorandum to former President Pratibha Patil outlining this demand. However, despite these efforts, the issue did not gain political support and failed to progress. Former Dahod MP Somjibhai Damor also initiated a movement for a separate tribal state, but it did not gain traction.

In April 2023, Chaitar Vasava, an AAP MLA and tribal leader, reignited the demand for Bhil Pradesh, citing injustice towards Gujarat's tribal population. He highlighted the allocation of thousands of hectares of tribal land for various projects in Kevadia, including the Statue of Unity, and the underdevelopment of tribal areas rich in water, timber, coal, and other minerals. The movement for Bhil Pradesh, under the BTP's banner, is currently gaining popularity.

Cultures of Different Bhil Tribes

The Bhil community is divided into several endogamous territorial divisions, each with its own clans and lineages. Here are some of the different Bhil tribes from various regions that you should know about:

Bhils of Madhya Pradesh and Chattisgarh

As per the 2011 Census of India, the Bhil tribe holds the largest population among tribes, with a total count of 4,618,068 individuals, making up 37.7 percent of the total Scheduled Tribe (ST) population. The Bhil tribe of Madhya Pradesh, concentrated in the Jhabua, Dhar, Khargone, Ratlam, and Neemuch districts is known for their handicrafts, carpets, ornaments, and fabrics. Although Chhattisgarh has a very less population Bhils about 547 people (Census 2011), the city of Bhilai in the Durg district of Chhattisgarh is named in recognition of the Bhil community, with "Bhil" signifying tribe and "ai" meaning came, indicating the origins of the Bhil people.

Jhabua Bhils are known for their ritualistic Pithora paintings, which are done only by men. The exquisite Pithora horses are painted by the lekhindra, the traditional painter, and offered to the devas. Legend has it that in the kingdom of Dharmi Raja, laughter, singing, and dancing had been forgotten. To restore these expressions, Pithora, the prince, embarks on a horseback journey to the abode of the goddess Himali Harda, who gifts them their happiness. These Pithora wall paintings also depict the Bhil creation myth. The wall art created on the houses of Bhil tribe was popularized by the pioneer Bhuri Bai, which came to be known as Bhil art. These Bhil paintings, characterized by a unique dotted style, vividly depict the folklore, prayers, memories, and traditions of the tribe. Renowned Bhil artists such as Bhuri Bai, Lado Bai, Sher Singh, Dubu, and Geeta Bhariya have gained recognition in India and internationally, celebrating the ritualistic and ancient art form. These art forms reflect the tribe's spiritual philosophies and deep connection with nature, highlighting their reverence towards the natural world. This connection is reinforced by their reliance on agriculture and animal husbandry as the mainstays of their economy.

Due to their agro-based economy, their colorful festivals and ceremonies revolve around rain and harvest. Bhagoria, their principal festival, thanks deities for a sizable harvest. Celebrated 10 days before Holi with traditional music and dance at village haats, the people arrive at haats with decorated bullock carts to partake in the year's biggest sales and purchases. The festival also celebrates love, romance, and marriage through elopement. Although the Bhil tribe forms a patriarchal society, their distinctive lifestyle includes different systems of marriage, which allow for freedom in the selection of life partners. While there is a bride price system, on one hand, there is a Bhagoria marriage of elopement on the other. However, as Bhils become more and more urbanized, their lifestyles and culture blend with modern ideas. They are constantly migrating to Bhopal, Kota, and Delhi as construction laborers as their lands have become ravaged by droughts in recent years. In the face of degrading environmental conditions, the Bhil tribes of Jhabua and Alirajpur districts have revived their centuries-old tradition of "halma", a place where the community gathers to find solutions for problems like water conservation.

Bhils of Gujarat

In Gujarat, Bhils living in Banaskantha, Sabarkantha, Panchmahal, Bharuch, Vadodara, Surat, and Dang districts make up 46% of the ST population in the state. In North Gujarat, they mingle with the Rajasthan Bhil and sub-tribes, while in Panchmahal, Vadodara, and Bharuch, they have close ties with Rathava, Dhanaka, Patelia, and Nayaka tribes of Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. Meanwhile, in South Gujarat, they interact with various tribes in the area, including those in Maharashtra. The Bhil community has several major sub-groups such as Bhil Garasia, Vasave Bhil, Pawra Bhil, and Tadai Bhil.

The Gujarat Bhils are known for their rich traditions of music and dance. Bhils sing songs to seek blessings from elders, ancestors, and deities at births and weddings. They perform the Garba dance during festivals and invite goddesses through their songs. Sometimes in the song, a devi replies that she cannot join the dance as her baby is crying. Bhil gods and goddesses are integral to their daily lives and their festivals.

In the Panchmahal district, the Bhils celebrate the Gol Gadhedo festival six days after Holi. Gol Gadhera is a game in which men attempt to climb the pole and reach the jaggery sweet, while the women drunk on traditional Mahua liquor are armed with sticks to deny men access to the pole. Whoever succeeds to reach the top and throws the price can ask any girl to marry him. In 1922, Thakkar Bapa, a social worker, founded the Panchmahal Bhil Seva Mandal to uplift the Bhil population from the crutches of poverty.

Unlike the social status of Panchmahal Bhils,the Dang Bhils form the royalty of the district. This place offers an interesting story from the colonial times. In the mid-1800s, the British made several attempts to capture the area, but the Dangs region, ruled by five courageous Bhil kings, remained unconquered. In 1842, however, the British secured a lease agreement with the tribal kings to exploit teak resources. During this time, the colonialists introduced the 'Dang Darbar,' a 15-day festival aimed at 'honoring' the kings. The darbar involved the kings riding on horses to receive their annual income, known as salyana. The first darbar took place in 1894. Today, this ritual from the colonial era is re-enacted annually in a three-day cultural extravaganza held in Ahwa, the district headquarters. While the trappings of nobility have faded and times have become frugal, the remnants of their princely status persist in an effort to maintain their power and status.

Bhils of Rajasthan

Like the Bhils of Gujarat are known for their traditional Garba, the Bhils of Rajasthan are known for their Ghoomar, which involves women taking rounds without losing balance. The religious dance drama of Than Gair is also performed by the men in the month of Sharavana (July and August). The Udaipur Bhils are also talented in sculptured work, carving beautiful horses, elephants, tigers, and Shiva deities out of clay.

Historically, Bhil kings once ruled the Vidhya regions and certain cities are named after them. Kota got its name from Kotya Bhil, Bansara is derived from Bansiya Bhila and Dungarpur is named after Dungariya Bhil. In pre-modern India, Rajput Rajas like Uday Singh and Maharana Pratap honored the Bhil chiefs by putting their figure in their emblems. The Rajputs recognized Bhil leaders as their allies, and the tribe leader, gameti, played a critical role in the coronation ceremony of Rajput kings. There were commensally and even connubial relationships between Bhils and Rajputs.

Bhils of Tripura

Unlike the Rajasthan Bhils native to their region since ancient India, the Bhil tribes of Tripura are nearly 100 years old. Migrated from their clan regions to work in the tea gardens of Tripura in 1916-17, the Bhil tribe settled in Tripura after independence. According to the 2011 Census, Tripura has a total of 3,105 Bhil population. Mainly engaged in tea gardens, brickfields, and agriculture work, the Bhil tribes of Tripura are located in Akinpur of Belonia, Bagan Bazar of Khowai Sub-Division. They continue practicing their generational Hindu customs despite their migration from their native lands.

Bhils of Maharashtra

With 2.5 million, Bhil tribe is a large tribe in Maharashtra constituting 21.2% of the ST population in the state. The Nirdhi and Tadvi Bhils of Maharashtra follow the Islamic faith. The Nirdhi Bhils reside in the Jalgaon District of Maharashtra, India, while the Tadvi Bhils inhabit the border areas of Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, and Maharashtra. These Bhil sub-groups have customs similar to other Muslim communities. However, their practice of Islam is not rigid, as they combine it with traditional and culturally Hindu lifestyles. The exact details of their conversion remain unclear. The Satmalas hills, which were part of the territory of the medieval Faruqi kingdom, played a significant role in the association between the Bhil community of this region and the Faruqi state, resulting in the conversion of many Bhils to Islam.

The community primarily consists of small and medium-sized farmers, with livestock raising as an important supplementary occupation. While most Nirdhi Bhils now speak Marathi, historically, they used their own Bhil dialect. The Tadvi Bhils speak their own dialect, known as Tadvi, but many are transitioning to Marathi. Their language also includes Dhanka and Bhilori, which belong to the Bhil group. Unfortunately, the Tadvi Bhil community has experienced instances of caste discrimination, leading to several cases of suicide.

Similarly, the Bhil tribe in Maharashtra, particularly in the Nandurbar district, has a long history of oppression and discrimination. They have been marginalized and denied basic rights, including access to education. In the past, Bhil Adivasis were largely illiterate, with limited opportunities for advancement.

Despite these challenges, Girdhar Noorapavara, a Bhil adivasi, and his team took the initiative to establish schools for Bhil children in 1991. However, they faced resistance from government officials who perceived the tribal community as incapable and treated them as "savages." The authorities attempted to shut down the schools and undermine their efforts.

The education provided by these schools went beyond traditional subjects, incorporating teachings on water, forests, and land. Students learned about the forest's herbs and edible tubers, understanding their uses. The learning environment was unconventional, with classes held under fallen trees and field visits to instill the importance of water and land. Their school, named "Jeevan Shala" or the "School of Life," symbolizes the emphasis on teaching life's truths. This discrimination persisted as the state government initially restricted Bhil students from attending general schools beyond grade 4. It was only through persistent protests and advocacy that the Bhil community secured the right for their children to take exams in mainstream schools. The Bhil community's commitment to education challenged prevailing oppression and empowered their children, allowing them to pursue education.

Bhils of Karnataka

The Bhil population in Karnataka comprises 6,204 individuals residing across various districts, with higher concentrations in Uttara Kannada and Belgaum districts. While limited information is available about present-day Bhil tribes in Karnataka, historical records offer intriguing insights. Known as Billavas or Bilia in inscriptions, they referred to themselves as Bedas, emphasizing their identity as hunters. According to Professor Hanuma Nayaka's research paper titled Situating Tribals in the Early History of Karnataka, these inscriptions reveal that the Billavas/Billas were renowned for their bravery and archery skills. Over time, they became integrated into the ruling class, assuming titles such as gauda, arasa, nayaka, and dannayaka.

As members of the state apparatus, the Billavas sought to elevate their social status. To achieve this, they actively participated in granting villages and lands to Brahmins and establishing agraharas, Brahmin settlements. Through these interactions, the Billavas gradually transcended their tribal identity and gained caste status.

Bhils of Sindh

The Meghwar Bhil community, also known as the Sindhi Bhil (ميگهواڙ ڀيل), is a sub-group of the Bhil people residing in the Sindh, Punjab, and Balochistan provinces of Pakistan. They have assimilated into Sindhi culture and are recognized as a significant Hindu community in the region. They are among the few Hindu groups in Pakistan who chose to remain in Sindh during the Partition of India.

The Meghwar community holds a low status in the Hindu caste hierarchy. Those residing in Punjab tend to be economically disadvantaged, working primarily as peasants and laborers across the country to sustain themselves. The Human Rights Commission of the United States has noted that feudalism continues to perpetuate slavery among the Dalit Meghwar Bhils, despite the 1992 law that officially abolished the slavery of Bhil groups to Pakistani landlords.

According to social anthropologist Hussain Ghulam's paper titled "Bhils of Pakistan," in Sindh and Balochistan, the situation for the Meghwars is dire, with many facing pressure to convert to Islam. Approximately 95% of Sindhi Meghwars reside in rural areas such as Badin, Thatta, and Mohrano, as well as cities like Mirpur Khas, Hyderabad, and Karachi. Some Meghwars and Kolis have converted to Ismaili Shia Islam in Khebar, Sindh. The Meghwar community speaks Sindhi Bhil, a distinct variety of Sindhi language with influences from Sanskrit. Some individuals also speak Marwari, Balochi, Sindhi, and Saraiki.