Thus Gotama (Buddha) walked toward the town to gather alms, and two samanas recognized him solely by the perfection of his repose, by calmness of his figure, in which there was no trace of seeking, desiring, imitating, or striving, only light and peace.

Resplendent in symmetry and replete with intricate patterns, Thangkas are Tibetan Buddhist paintings that are intimately linked with the lives and teachings of Buddha, the Enlightened One. The Nepalese term for Thanga paintings is Paubhas. Historically, Thangkas have been created on cloth since the 11th century, following the revival of Buddhism. It would be an error on our part if we were to confine this complex and creative art to just this sole theme, as Thangka is known to encompass an extensive array of iconographies and ideas along with a montage of motifs.

These motifs include the Chakka (or the Wheel of Dhama- a symbol of wholeness, perfection, and more), conch shell (symbolizing a deep and melodic sound of the dharma), victory banner (this represents Buddha’s victory over 4 Maras or hindering forces), and the lotus (understood as the symbol of spiritual purity). White Tara, Maitreya, Jataka stories, Sakhyamuni Buddha, and Tibetan astrology are some of the other recurrent themes of Thangka.

Creating Thangkas is believed to involve a spiritual journey of sorts, thus no two Thangkas are alike. Every Thangka, thus, is a mirror reflecting the painter’s mystical journey through his act of creation.

A Thangka, with its dexterous employment of geometric patterns, could depict a Mandala, a deity, or any event in the life of Gautam Buddha. Since its conception, these paintings have been done on cotton or silk appliques. In this blog, we will primarily deal with the varieties of Thangkas based on their background colors, techniques figures:

Thangka serves as a meditation tool, offering the artist/practitioner the freedom to creatively explore and play with the colors to externalize the inner world. That’s why no two thangka artworks are identical. Even the same artist cannot replicate their own work precisely because each meditative journey is different.

Based on color, the Thangkas can be categorized into 4 types

- Golden Thangka

- Black Thangka

- Multicolored Thangka

- Red Thangka

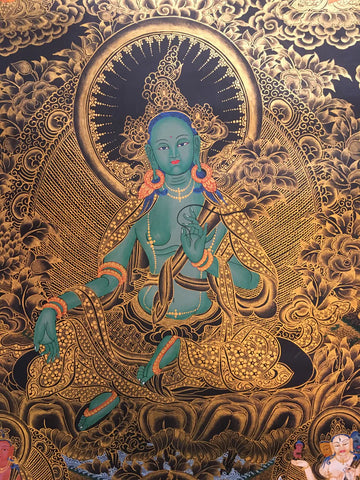

Golden Background

Golden Thangkas, as the name suggests, are characterized by the extensive use of gold. These Gold Thangkas are reserved for serene deities and enlightened Buddhas, symbolizing auspicious blessings and divine radiance. In an Eastern parable, a spiritual Lama invited two gifted artists to create a golden shrine. He described a vision of a radiant gold figure that he had for the artists. Their artistry brought the figure to life, so vivid and animated that it transcended the art itself. The Tibetan term for such divine artistry is Serhu Jazer Ma which roughly translates to gold images with a divine radiance.

Multicolored (Tib.) tson-tang

There is no doubt that multicolored Thangka paintings are the most popular type of Thangas. They offer artists ample room for creative space. Consequently, the usage of varied color-palettes is very much evident. Multi Colored Thangka art, with its diverse color palette, also encompasses a wide array of subjects including Palas or the illustration of deities, Mandalas, anecdotes or historical events. This results in a great deal of communication expression and stylistic variations. Indeed, these Thangka artworks are not only visually stunning but also carry deep philosophical significance.

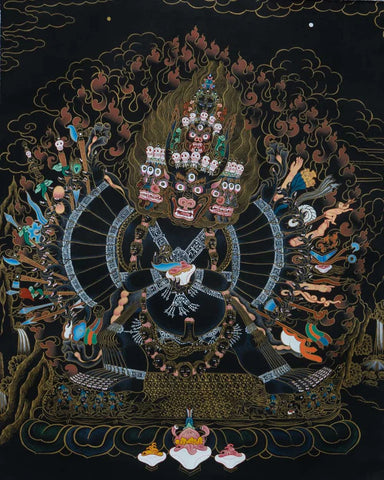

Applique (Tib.) nag-tang

Nag-Tang refers to a golden line set against a black backdrop. Wrathful Tibetan deities are often depicted in black and gold Thangas. The black background, perhaps stands for the unknown while the golden figure represents the fierce as well as the enlightened nature of these beings. At times, one can also observe the presence of the fire element artfully conveyed through symmetrical, sinuous, swirling patterns. Nag-tang can be viewed as an intense and powerful expression whereupon the transformative and protective aspects of these deities are brought into the limelight.

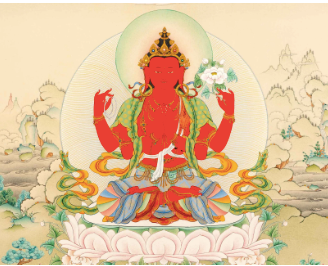

Red Background (Tib.) mar-tang

Red embodies various significant elements: wrath, prosperity, enlightenment and compassion, particularly within the context of Bodhisattva, like Chenrezig (or Avalokiteshvara). In this context, Thangka paintings depict the tender and compassionate side of the deities. Yet, it is crucial to acknowledge that the color red is also employed to depict Shakti/power and wrath.

Depending on the techniques, Thangkas can be further categorized into several types, which include lacquered thangka, embroidered thangka, brocade (tshen-drub-ma), pearl inlay and applique.

Based on technique, the Thangkas can be categorized into 3 types

- Those that are painted/ Palas

- Silk applique/Dras-drub-ma

- Block Thangkas/Dpar Thangka

Palas

“Palas”, typically refers to illustrative paintings of deities and sacred figures. The artists employ pigments, dyes and brushes to paint the intricate designs and religious imagery on the canvas. In this method, gesso or chalk is applied to the white cotton or linen frame. This provides a base over which outlines are drawn before the color is applied. Palas is done with utmost devotion and dexterity.

Dras-drub-ma/ Applique Thangka

As with paintings, Thangka applique is a sacred art form. The applique Thangka is created not based on paints but using patchworks of numerous patterned silk fabrics. The art of Applique first began in the Huns community of Central Asia. Eventually, it spread east along the Silk Road and was fervently adopted by Tibetans.

Dpar Ma/ Block Thangka

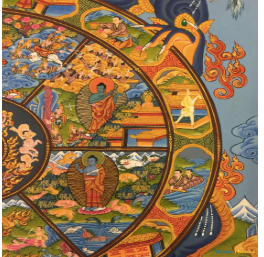

These Thangkas are created on canvas using block printing techniques that expedite the painting process. This technique involves printing the outline of the Wheel of Life before applying colors, significantly speeding up the time required for completion.

Further classification of Thangkas can be based on the subject depicted within them. For instance:

- Bhavacakra/ Wheel of Life

- Yidams

- Dharmapalas/ Wrathful Deities

- Peaceful Deities

Bhavacakra/ Wheel of Life

The Wheel of Life is geometrical and it is known as Bhavachakra in the Sanskrit language. They illustrate the teachings of Shakyamuni Buddha. Formed by the combination of two words, “Bhava” and “Chakra”, the term signifies the rotational nature of worldly existence/Samsara. It encompasses both our external circumstances and inner experiences. The Wheel of Life incorporates all the topical elements found in Buddhism, for instance, the Four Noble Truths, the origin and the cause of worldly sufferings, and the impermanence of existence.

Yidams

Fully enlightened beings are represented by Yidams. Yidams are personal meditation deities, chosen by practitioners for their spiritual journey. They are special in the sense that they help those who consider themselves serious practitioners to either empower or overcome specific aspects of themselves. The symbols and the imagery used in this case are believed to be a little more complex than perhaps most of the other classes of Thangkas.

Dharmapalas/Wrathful Deities

The 8 Dharam-palace or the protectors of Dharma, the Istadevatas/ personal gods are the common subjects of these Thangkas. Vajrabhairava, Vajrakalika, Yamantaka, Hayagriva, and Kubera are some of the most common types of wrathful gods that find their place. It is crucial not to mistake wrathful deities for demons, despite their frequently fearsome appearance. Dharmapalas are considered to be the protectors of minds from pessimism and to lead us on the path of converting that negativity into positivity.

Peaceful Deities

Peaceful deities are probably the largest class of deities in Thangka art. Among the Dharmakya forms, we find peaceful deities such as Samantabhadra, and Amitabha. Within the Sambhogkaya forms are beings like Amitayus and Manjushree. Lastly, in the Narmakaya categories, we have Padmasambhava. There is an immense amount of precision involved in creating these serene faces. Wisdom, compassion, and mindfulness are some of the characteristics that are brought forth in this collection. The inclusion of sem-wrathful deities can also be seen here.

Conclusion

From the 14th century onwards, Chinese techniques and styles had a significant influence on Tibetan art. By the 18th century Tibetan paintings not only echoed but also seamlessly influenced numerous elements from other parts of India. The exclusivity that Thangka has amassed over time has remarkably enhanced its quality. Within the Thangka artistry, the creator is more than just an illustrator; they are a seeker, a mediator, a soul on a profound journey. There is still a lot to explore and uncover in the realm of Thangka art.

- “Thangka, an Introduction to Tibetan Art.” Enlightenment Thangka, October 6, 2023. https://enlightenmentthangka.com/blogs/thangka/thangka-tibetan-art.

- “The Process of Thangka Painting - Google Arts & Culture.” Google. Accessed February 28, 2024. https://artsandculture.google.com/story/the-process-of-thangka-painting-dastkari-haat-samiti/-QWh8YagYf4tIQ?hl=en.

- “The Thangka and Its Significance in Tibetan Buddhism.” Invaluable, July 21, 2020. https://www.invaluable.com/blog/thangka-tibetan-buddhism/.

- Bhatta, Sailendra. “Thanka Painting in Nepal: Discover the Rich Tradition.” Nepal Travel Vibes, May 8, 2023.

- https://www.nepaltravelvibes.com/thanka-painting-in-nepal/.

- Santi, Bhikkhu. “Getting the Ball Rolling.” Tricycle, January 31, 2023. https://tricycle.org/magazine/translation-buddhas-first-teaching/.

- “Many Secrets of the Thangka Painting and Thangka Painting in Nepal.” Yuna Handicrafts Nepal, February 21, 2023. https://yunahandicrafts.com/blog/thangka-painting-nepal/.

- Long, Leon. “Thangka Painting - the Encyclopedia of Tibetan Culture.” Thangka Painting | The Encyclopedia of Tibetan Culture, June 20, 2023. https://www.chinaeducationaltours.com/guide/culture-thangka-painting.htm.

- “Appliquéd Thangka.” Norbulingka Institute of Tibetan Culture (India), July 22, 2020. https://india.norbulingka.org/blogs/news-from-dharamsala/appliqued-thangka.

- “Silk Applique.” D’Source, December 23, 2015. https://www.dsource.in/resource/silk-applique-thangka-himachal-pradesh/introduction.

- “Wrathful Deities.” Thangka Mandala. Accessed February 28, 2024. https://www.thangka-mandala.com/thangkas/wrathful-deities/#:~:text=The%20main%20group%20of%20wrathful%20deities%20that%20almost,his%20various%20forms%2C%20Hayagriva%2C%20Yamantaka%20and%20Kubera%20%28Jambala%29.